Categories:

Energy

/

General Market Commentary

Topics:

General Energy

/

General Market Commentary

Blue Sky Uranium Looking to Significantly Increase Resource of Flagship Ivana Uranium-Vanadium Project

The Critical Investor takes a look at the fundamentals for uranium and profiles a company with a uranium-vanadium property in Argentina.

1. Introduction

After publishing the results of the Preliminary Economic Assessment (PEA) for its Ivana uranium/vanadium project in Argentina on February 27, 2019, and filing this study recently on April 12, 2019, Blue Sky Uranium Corp. (BSK:TSX.V; BKUCF:OTC) positioned itself immediately as a low-cost development play in the uranium mining sector. At a low base case uranium oxide (O3O8) price of US$50/lb U3O8, the after-tax NPV8 is US$135.2 million and the IRR is 29.3%. These are very decent numbers as most competitors use US$60–65/lb U3O8 for their base cases. Initial capex is US$128.05M, and the all-in sustaining costs (AISC) net of vanadium credits is US18.27/lb U3O8. This AISC is amongst the lowest in the industry.

This doesn't mean that the entire project is economic at this time as the long-term (or also called contract) uranium oxide price is US$32/lb U3O8 (Source: Cameco), as is any project worldwide except the ISR operations in Kazakhstan and Arrow of NexGen Energy, but it sits at the front of low-cost projects and operations. It is believed by market experts that contract prices need to increase to at least US$50/lb U3O8 before any new project gets developed into a mine, and there are many different views around on this pricing topic if and when this could occur. Blue Sky Uranium has made its mark now, and sets out to potentially grow its flagship Ivana deposit considerably, which in turn could improve economics even further. What this could mean for investors will be discussed in the following article.

All presented tables are my own material, unless stated otherwise.

All pictures are company material, unless stated otherwise.

All currencies are in US Dollars, unless stated otherwise.

2. Company

Blue Sky Uranium is an exploration and development company, focusing its uranium and vanadium exploration efforts on southern Argentina, with 100% control of more than 434,000 hectares of mining tenures. The company is a member of the Grosso Group, led by Joe Grosso, and is a resource management group that has pioneered exploration in Argentina since 1993.

The company's Amarillo Grande Uranium-Vanadium Project in the Rio Negro province is a district-scale uranium discovery and includes the flagship Ivana project, containing the country's largest NI 43-101 resource estimate for uranium, with a significant vanadium credit.

Blue Sky Uranium currently has 109.79 million shares outstanding (fully diluted 157.61 million), 43.3 million warrants (the majority is due @C$0.30–0.35 in 2020), and several option series to the tune of 4.5 million options (C$0.30, expiring at Jan 23, 2023) in total, which gives it a market capitalization of C$24.7 million based on a April 14, 2019, share price of C$0.225.

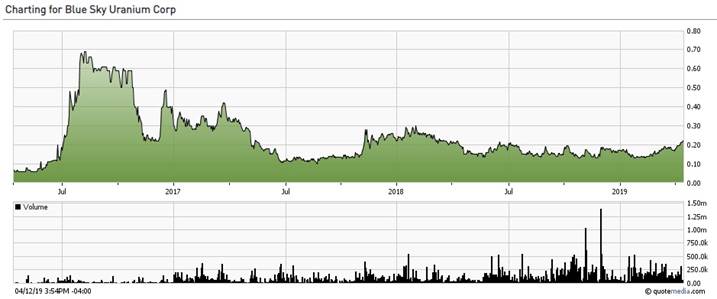

The company has no trouble raising cash despite the difficult sentiment for the last year or so, as it raised C$3.4 million in June 2018. This kind of money goes a long way for exploration (drilling) at the Ivana project, as all mineralization is very near surface, at a maximum depth of just 30m, and the host material is soft unconsolidated gravels and sands. The share price showed a bit of a pulse after the PEA results were released last February, but it will be clear that the stock is just coming off bottom levels, which formed strong support:

Share price; 3 year time frame

This is predominantly related to the current low uranium prices for spot and contract, rendering almost all uranium projects worldwide uneconomic as mentioned, making the uranium juniors and miners an unloved niche sector at the moment. The uranium market itself is a very intransparent and therefore complex market to understand and surely forecast, but I will try to make things a bit more insightful in the next section.

The management team is the core of the Grosso Group team, and is led by President and CEO Nikolaos Cacos, who has been with the Grosso Group since inception in 1993, and a director of Blue Sky Uranium since 2005, and a director of Golden Arrow Resources since 2004 and president and CEO of Argentina Lithium since 2013. All three companies are members of the Grosso Group, and operate in Argentina. CFO Darren Urquhart isn't that long with the group but also closely involved like Cacos as he is CFO of all three companies. With all three companies there is a specific metal specialist geologist on board, and with Blue Sky it is Guillermo Pensado, the VP of Exploration and Development, who has over two decades of experience in exploration and economic project assessment in the Americas, with most of it focused on uranium.

When we are talking about the Grosso Group, there is no way we can go around the founder and president, Joseph (Joe) Grosso. He became one of the early pioneers of the mining sector in Argentina in 1993 when mining was opened to foreign investment, and was named Argentina's "Mining Man of The Year" in 2005. His knowledge of Argentina was instrumental in attracting a premier team, which led to the acquisition of key properties in Golden Arrow Resources' portfolio, of which the development of Chinchillas eventually resulted in a JV with SSR Mining. He has successfully formed strategic alliances and negotiated with mining industry majors such as Barrick, Teck, Newmont, Viceroy (now Yamana Gold) and Vale S.A., and government officials at all levels. At the moment he is the chairman of Blue Sky Uranium, a director of Argentina Lithium, and executive chairman, CEO and president of Golden Arrow Resources, which is the flagship company of the Grosso Group.

To me, Grosso is instrumental in managing any jurisdictional risk in Argentina, and very important for Blue Sky Uranium in this role. So far for management, let's have a look at the commodity in focus, which is of course uranium.

3. Uranium

Uranium (chemical element U, better known as U3O8) in its pure form is a silvery white metal of very high density—even denser than lead. Uranium can take many chemical forms, but in nature it is generally found as an oxide (in combination with oxygen). Triuranium octoxide (U3O8) is the most stable form of uranium oxide and is the form most commonly found in nature.

Canada, Australia and Kazakhstan are estimated to account for over half of the world's resources of uranium, which are estimated to total approximately 4.74 million tonnes. Australia has approximately 30% of world resources, Kazakhstan 17% and Canada 12%.

Many industrialized nations are heavily dependent on nuclear power generation, with nuclear electricity representing a major component in such countries as the United States (21%), Hungary (36%), Sweden (46%), and particularly France (78%) and Lithuania (80%). As renewable energy (wind, water, solar) is becoming increasingly important, but it's main issue is its lack of continuity, society needs sufficient base load power, and coal and nuclear can provide this certainty, and therefore will not go away anytime soon, especially nuclear.

Worldwide, there are 448 nuclear power reactors operating in 31 countries with total installed capacity of 392,000 MWe. The scale of the world's nuclear industry is considerable and uranium demand is projected to be growing again after Fukushima created havoc and Germany and Japan were facing closures of their nuclear fleet. Japan used to be one of the biggest nuclear electricity producers (34%), but since the Fukushima disaster in 2011 all nuclear reactors have been shut down. Since Q3, 2014, Japan is slowly restarting reactors again, which caused some optimism regarding the uranium prices, but the latest news is the Japanese courts are hesitant to approve restarts, and only granted approval for seven reactors so far. The government is very pro nuclear energy so expectations about the prospect of a fleet wide restart remain high.

As of January 2019, there were 58 reactors under construction, 167 planned (approved and funded) and another 345 proposed (intended but not approved or funded). New construction is currently concentrated in Asia with China and India in the forefront. There are also a number of reactors being phased out, so it is expected around 2020 to have a net addition of 50–60 reactors worldwide, of which the majority will be located in Asia.

An important development are the production cuts by Cameco and Kazatomprom as a reaction on ongoing low uranium oxide prices. In general, US$60–65/lb U3O8 is believed to be the minimum threshold to bring most idled operations back online again, or start up new mines.

Uranium prices; Source Cameco

Cameco even shut down its flagship McArthur River Mine last year, the world's largest high-grade uranium mine, for an indefinite period of time, besides Key Lake. This meant it has put its mines on care and maintenance, laying off most of its staff (even firing 150 people at headquarters) at undoubtedly a hefty price tag, and this means it will take a lot of time and much more money, and therefore much higher uranium prices, to restart it all again.

Necessary pricing could involve US$50/lb U3O8 levels, and maybe even higher, as it is rumored by experts that the McArthur River mine needs a complex, difficult and expensive expansion to mine the next phase. It is even suggested that it would be cheaper to buy and build Arrow, the Tier I deposit of NexGen Energy, and this seems valid on the longer term as Arrow appears to be much more profitable than McArthur River or Key Lake at the moment. In the meantime, Cameco fulfills its delivery duties by buying in the spot market, buying that could reach as much as 20M lb U3O8 this year.

Cameco is not the only one doing this, as for example traders, banks and hedge funds are buying uranium oxides left and right in order to speculate on future price increases. A new fund, Yellow Cake PLC, has an offtake agreement in place with Kazatomprom, which accounted for the buying of 8.1M lb U3O8 at the discounted price of US$21.01/lb U3O8 in 2018, and gives Yellow Cake the possibility, not the obligation, to buy large quantities for the next nine years, to the tune of US$100 million each year.

World uranium production is dominated by Kazakhstan, Canada and Australia, which, together, produce about 74% of annual mine supply. These countries are followed by Niger, Russia and Namibia. These leading producers combined account for approximately 95% of worldwide mine production. In 2018, world production of uranium was estimated at about 123M lb of uranium. The four largest producers, Kazatomprom, Cameco, Orano (former Areva) and ARMZ-Uranium One, have a market share of 65%. In 2018 worldwide production of uranium came from underground (34%), open pit (24%) and ISR mines (36%).

Prices of uranium are always, just like gold, subject of widespread sentiments and not the result of a healthy supply/demand mechanism, although the uranium markets are well known by the number of utilities (the nuclear power plants) in production, under construction, etc. Something that isn't very well understood however, but obviously key to demand, is the stockpiling by utilities, usually by fulfilling their long term contracts, like the Japanese appeared to be doing during the shutdown since 2011. Because of this, the markets expected a huge stockpile to come on the market sooner or later, when it would be clear Japan would dismantle its nuclear reactors. This development didn't pan out as we know now, and it is expected that Japanese utilities will enter the LT markets in a few years after they restarted. It is also expected that not all Japanese reactors will be restarted, so in my view there should be a lot of idle stockpiles available for restarting utilities.

It is widely agreed upon that the growing net number of reactors will eventually generate increased demand, which would in turn create shortages based on current supply levels. However, this can take a few years to materialize.

Olympic Dam, BHP, Australia

Uranium oxide supply isn't switched on in a short period of time, and an increase in demand by utilities can't be met by the mining industry in time, and this is the catalyst all uranium investors are waiting for. It will probably take at least one year to have McArthur River and Rabbit Lake back online again, and the same or even longer goes for existing or new ISR operations of Kazatomprom. It recently said it could add 7M lb U3O8 of production annually by investing US$100 million many times over, but ISR is slow to ramp up, it takes about 18 months after the wells are in place.

Besides this, there is spare capacity waiting in Australia (Olympic Dam, BHP) which will likely be expanded as soon as uranium contract prices improve meaningfully, and the Honeymoon Mine (Uranium One), which was closed in 2013 due to low prices and would be reopened in that case, and possibly Kazakhstan, currently globally the largest producer. In Namibia there is the Langer Heinrich (Paladin Energy) mine waiting for better times, but it will be clear that new production capacity will take a lot of time. And the Chinese-owned Husab mine is coming online this year. But all these mines and projects have one thing in common: it takes time, to the tune of 1.5–2 years. And when the spot market has dried up and utilities start buying, there is no time. Much has been made of current stockpiles of utilities, but most of these stockpiles are government owned and will not go back to the markets again.

According to the World Nuclear Association, global demand is expected to rise to 180M lb U3O8 in 2025, supply will be an estimated 140M lb U3O8 at the time, including restarted McArthur River, Key Lake and Kazatomprom mines.

Another issue that might influence supply/demand is the Section 232 investigation, which looks into the potential for imported goods to harm national security, and uranium is one of them. A proposal by Ur-Energy and Energy Fuels has been made for a 25% quota on domestic uranium, whereas domestic production is not even 1% at the moment. The ramping up production of Kazakhstan since 2005 at very cheap prices has effectively put most U.S. producers out of business. A large part of this Kazakh production went to China, which has massive stockpiles, accounting for more than half of total stockpiles worldwide.

An organization representing utilities, the Ad Hoc Utilities Group (UHAG) is vehemently opposing this proposal, as such a quota could cause a dramatic spike in uranium prices, which in turn, according to them, could threaten 100,000 direct jobs and 475,000 indirect jobs. It could also force the U.S. to deplete its own stockpiles at rapid pace, as sufficient new production coming online would take a long time and a huge amount of money. I believe these to be unrealistic claims as unprocessed uranium costs only about 6% of total costs for utilities, and such a spike could cause an estimated $300–500 million increase in fuel costs for the top eight utilities, but at the same time their combined net income for 2017 was US$18.8 billion, so they have quite a bit of margin in my view. The UHAG furthermore denies the dependency of the U.S. on uranium imports from potential enemies like China and Russia, but this is not true as Canada and Australia accounted for almost 60% of U.S. uranium supply, and Kazakhstan delivered another 11%.

This last country enjoys a very strong relationship with the U.S. as a NATO partner, and has no close relations with Russia, on the contrary. As the uranium mining industry in the U.S. is very small (under 500 people work there), it is very likely to see the utilities as a much larger industry having more (political) impact in this discussion. I expect them to mobilize quite a bit more potential presidential campaign donors and influential Republicans so I don't believe the 25% quota to make it. But on the other hand, Trump is Trump, always looking at money, protectionism and enemy countries, so you never know. Anyway, it is very hard to provide a meaningful forecast for something as speculative as the uranium price as there is no transparent market.

What is the situation in Argentina these days regarding nuclear energy?

Argentina has three nuclear reactors generating about 5% of its electricity. Its current annual consumption is approximately 300 tonnes U3O8 (or 660,000 lb U3O8). The country's first commercial nuclear power reactor began operating in 1974 and collectively the three plants produce 1667 MWe. The current reactors include a CANDU 6 and a Siemens design; the next two planned reactors are to be built by China National Nuclear Corporation. Additionally, five research reactors are operated by the National Commission of Atomic Energy (CNEA) and others.

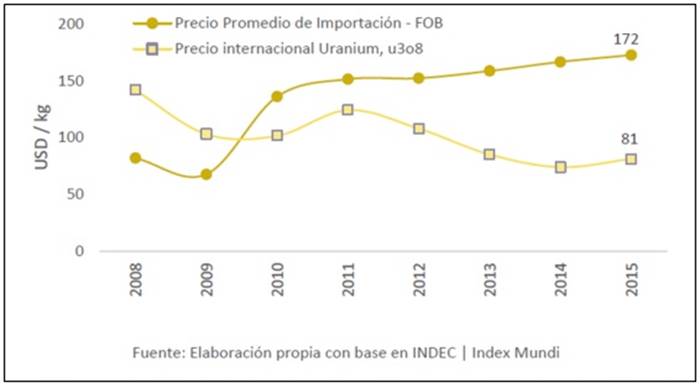

Two further research reactors are under construction. The CAREM-25 nuclear reactor, which has been developed by CNEA with INVAP and others, since 1984, is a modular 100 MWt simplified pressurized water reactor designed to be used for electricity generation (27 MWe gross, 25 MWe net) or as a research reactor or for water desalination. The prototype will be followed by a larger version, possibly 200 MWe with potential to upscale to 300 MWe. Sites in Argentina and internationally are being considered for the CAREM-25. Argentina requires 100% importation of its uranium supply. As shown in Figure 19-1 below, sourced from the Mining and Energy Industry of Argentina, the 2015 price paid for uranium was more than double the international market price for uranium.

It doesn't look like this situation will be solved anytime soon in Argentina, and provides an excellent environment for Blue Sky and the Grosso Group to negotiate with the government on long-term contracts.