Categories:

General Market Commentary

/

Precious Metals

Topics:

General Market Commentary

/

General Precious Metals

Cerro Rico – The greatest of the great

In this column on great deposits, I have discussed those that were rich, big, changed destinies, broke governments and accumulated a wealth of stories. However, only one has definitively changed the world. Cerro Rico, or Potosi in Bolivia, is perhaps the greatest of the great deposits. It’s origins are shrouded in myth, the wealth proverbial, the toll horrific. The Cerro Rico was the keystone in the arch of colonial Latin American precious metal deposits whose combined wealth provided the single greatest metallic bonanza there was, and likely will be on earth. Eduardo Galeano has said ” You could build a bridge of pure silver from Potosi to Madrid with ore extracted. And you could build a bridge back with the bones of those who died mining it”

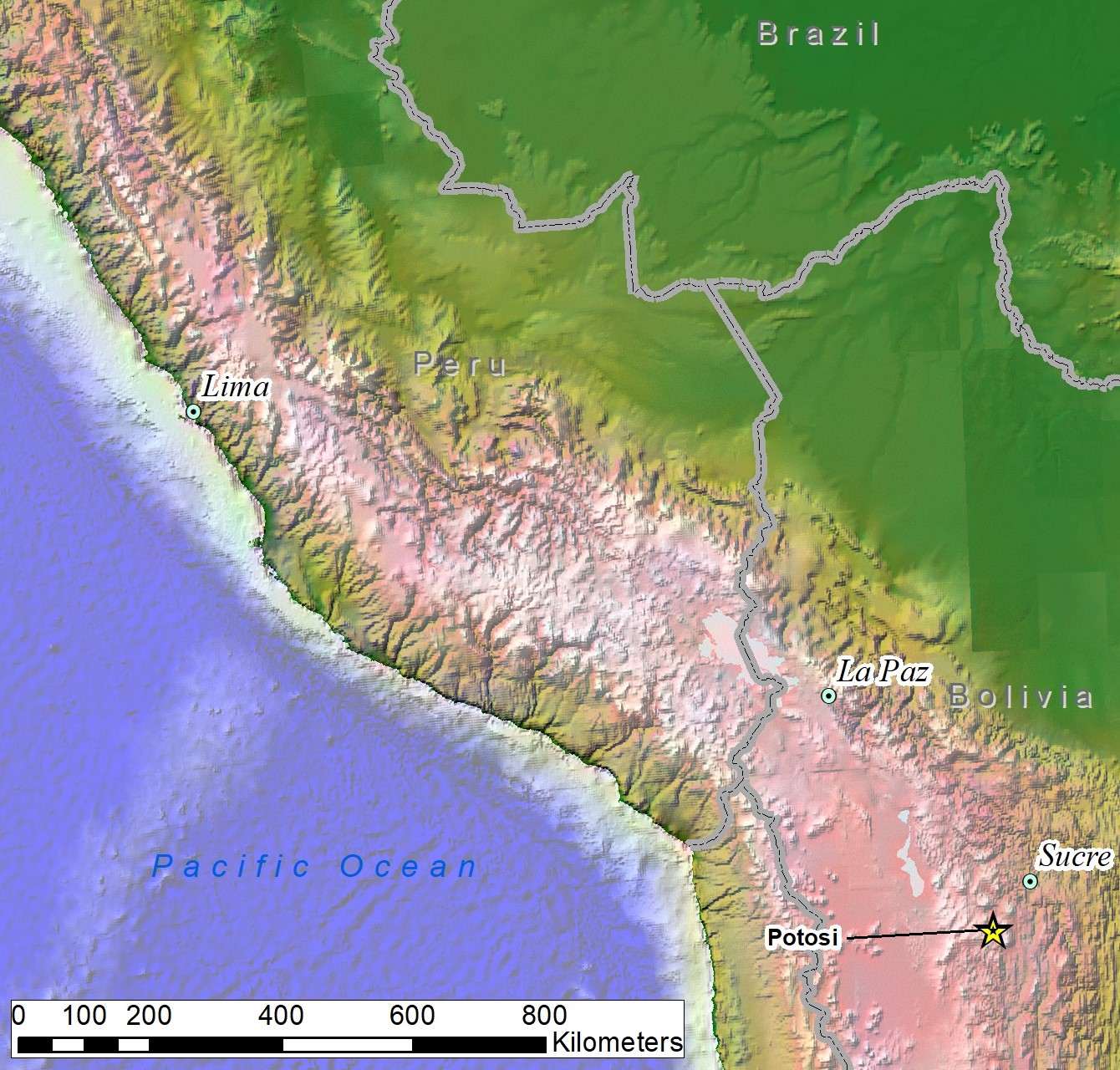

Location of Potosi in Bolivia

By 1545 Spain had consolidated it’s hold on the it’s new empire. The Aztecs had fallen a quarter century earlier, the Inca’s by 1533 and they were fanning out looking for more. Depending on the story either the Inca discovered the deposits, but were warned off by spiritual forces who terrified the would be miners (giving it the name Potoji ,”thunderous” in Quecha), or a shepherd looking for his lost sheep built a fire and noticed the trickle of molten silver, or as the archaeology of nearby lake sediments suggests the deposits were known and exploited for over 400 years before the Spanish showed up. However it started, word soon got out, and a city of 160,000 sprang up on the cold, windy barren plain, 4000 metres above sea level. This would be akin to a gold rush town of 2,000,000 springing up today. It had a magnetic attraction with thousands and thousands of people arriving every year. From friars to Medici’s to princes to prostitutes all rushed in. In Potosi, the horses were shod in silver(so it was said), and the riches of the world flooded in. Silks, from China, cotton from India, slaves from Africa, and more mundane goods such as iron, imported from the Basque region of Spain and mercury from Slovenia. A mint was established in 1575 and soon it was producing up to 5,000,000 silver coins a year. These coins were known as “pieces of eight” from their divisibility into quarters the eighths. They remained legal tender in many areas of the world well into the 19th century.

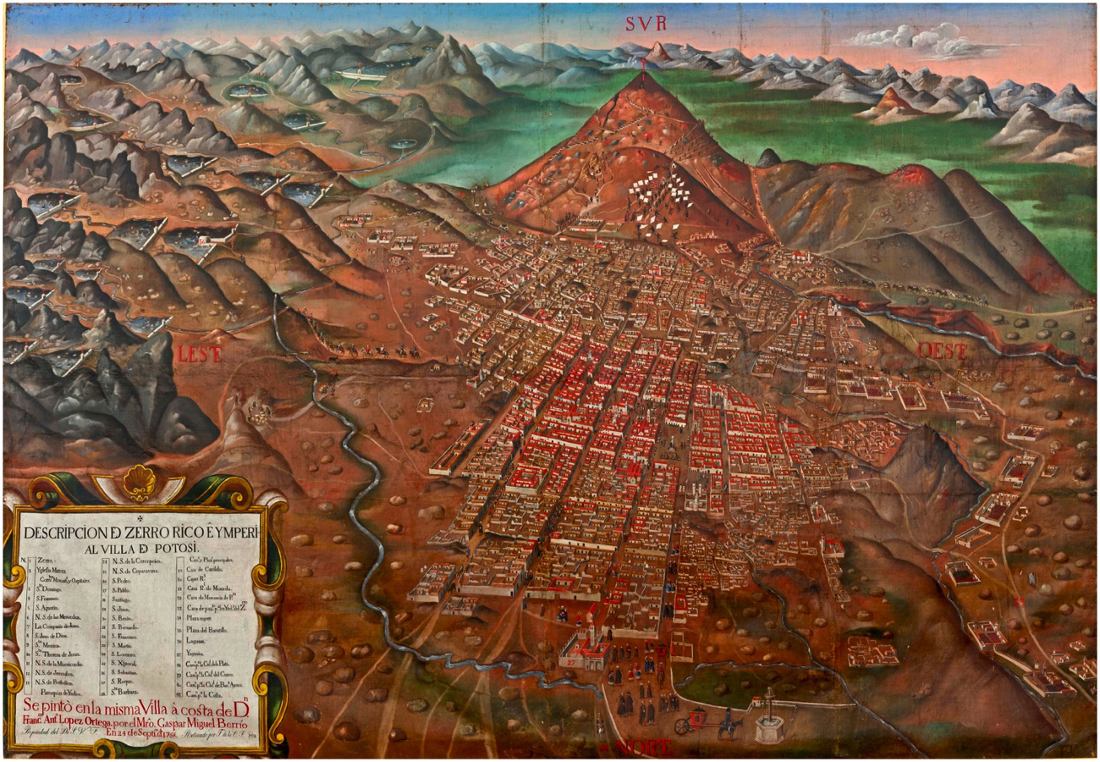

Potosi in 1745. The reservoirs to the left (east) were used for washing ore.

From 1545 to 1650 the silver from Cerro Rico alone out produced all the silver districts in Mexico. Grades of up to 40% silver (>12,000 ounces per tonne) are reported and 4% silver was the average. Early mining technology was basic with clay furnaces (huayras) powered by Llama dung and moss . These were highly efficient at smelting the high grade oxide ore. However, when that ran out the Vicery of Peru Francisco de Toledo introduced the patio process. Originally from Mexico, silver sulphide ore was crushed with mercury in arrastras, stirred and mixed with reagents in the open air on large “patios” to enhance the reaction over a few weeks. This formed an amalgam of native silver and mercury. Mercury was then burned off yielding pure silver. The small matter that the nearest mercury deposits were 1000 kilometres away, in what is now Peru, didn’t phase the Spanish, they simply imported African slaves and re-introduced the Inca labour tax, the mita. This was the system of mining and processing that earned Cerro Rico the title “The mountain that eats men” . The mercury was mined in horrendous conditions which practically guaranteed an early death (apparently when the bodies rotted, they left small pools of mercury). At the Cerro Rico, a Spanish crown deeply in debt and dependent on the stream of silver, introduced a daily quota of 25 sacks of 45 kilograms ore. By this time (1572) most of the easy to work veins had been mined out. So mining continued hundreds of metres below the surface, in humid damp unsanitary, conditions, subject to all the risks of 16th century mining. The upper estimate for the people killed mining in Potosi in the colonial period is 8,000,000. How much silver came out? Estimates range from the 1,000,000,000 ounces to 2,000,0000,000 ounces. All we know for sure is that 756,000,000 ounces were reported to the Spanish crown.